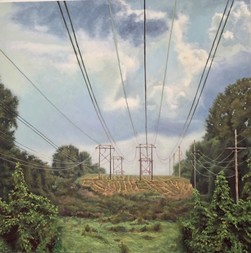

"Scrub on a Hill", oil on canvas, 36"x36"

"Scrub on a Hill", oil on canvas, 36"x36" My latest painting "Scrub on a Hill", attempts to literally upend the conventions of landscape painting by forcing a dynamic of vertical movement. Landscape, by definition, infers a horizontal axis; hence, the computer matrix "landscape/portrait formats.

But my objective in this painting is to move the viewer through and upward rather than across the space. I first squared the composition in order to equalize the vertical and horizontal and then employed practically every pictorial device to emphasize the third dimension (depth) and upward thrust.

But my objective in this painting is to move the viewer through and upward rather than across the space. I first squared the composition in order to equalize the vertical and horizontal and then employed practically every pictorial device to emphasize the third dimension (depth) and upward thrust.

These devices include linear perspective properties of scale and pronounced sight lines; atmospheric perspective properties of contrast and detail; drawing means of line, value and texture; and color properties of hue, value and temperature. Additionally, I borrowed a landscape design device of compartmentalizing the space into "rooms" in order to enhance spatial movement.

The result is fairly quick movement from foreground, up and over the slight hill, and then reverse movement back and up to the clouds. The movement is quick but the air is thick; a hot summer atmosphere. This is the full, deep, relentless green of mid-summer: nothing like the broad color range of my usual late fall/early spring landscapes. And this was the most difficult aspect of the painting.

The result is fairly quick movement from foreground, up and over the slight hill, and then reverse movement back and up to the clouds. The movement is quick but the air is thick; a hot summer atmosphere. This is the full, deep, relentless green of mid-summer: nothing like the broad color range of my usual late fall/early spring landscapes. And this was the most difficult aspect of the painting.

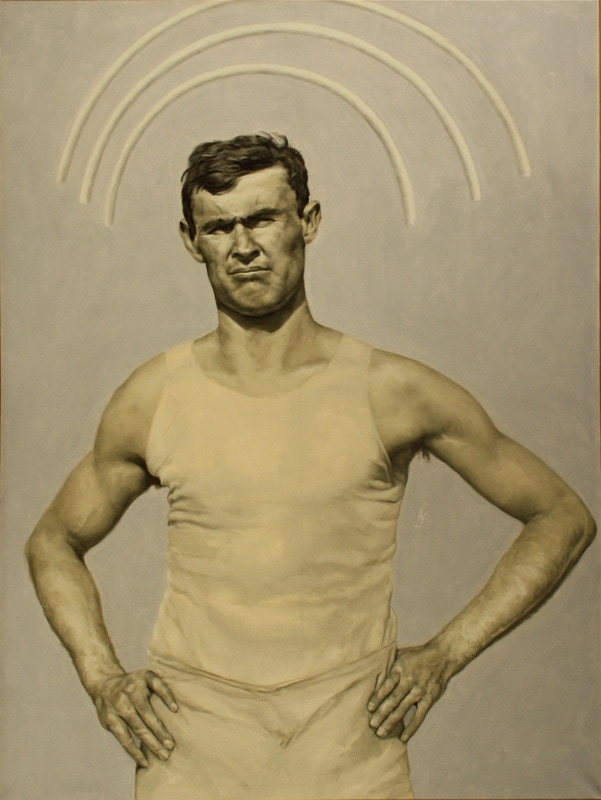

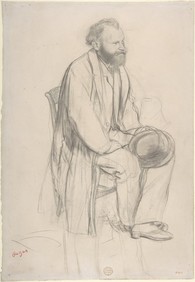

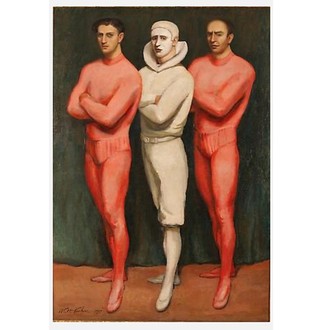

Neil Welliver, "Shadow"

Neil Welliver, "Shadow" Green paintings are the most difficult which is why there are so few of them. The great landscape painters like Corot, Inness, and Welliver employed green very sparingly and never produced green paintings.

The greatest painter of green, Henri Rousseau, created surrealistic dream-like images, capitalizing on green's psychological qualities. This is the approach taken by Gillespie and Kelly more recently, which I have sometimes tried to emulate in some of my figure paintings.

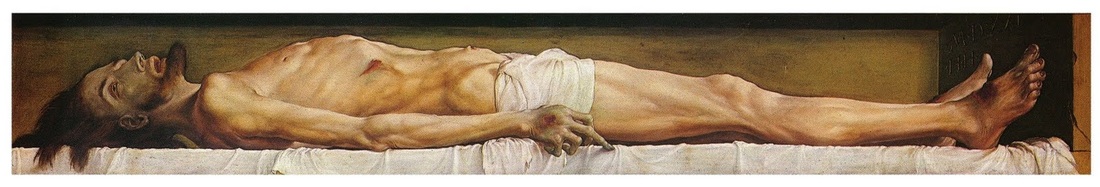

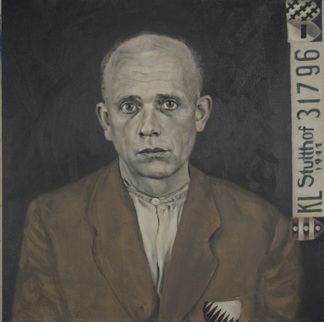

Henri Rousseau, "Dream"

Henri Rousseau, "Dream" Green is so difficult to depict, especially in direct observation, because it doesn't exist. What we perceive as green is really variations of yellow and blue. And those perceptions are determined by the type of red (orange, red, violet) next to it. It is impossible to depict green with green pigment.

I am particularly happy with the title, "Scrub on a Hill". I have an on-going argument with my colleague, Jacob Stanley, on the purpose of titles. He believes in the importance of titles as qualifier while I insist their role be limited to identifier. I am a strong believer that the image needs to stand on its own and is deficient if it needs to be "completed" with words.

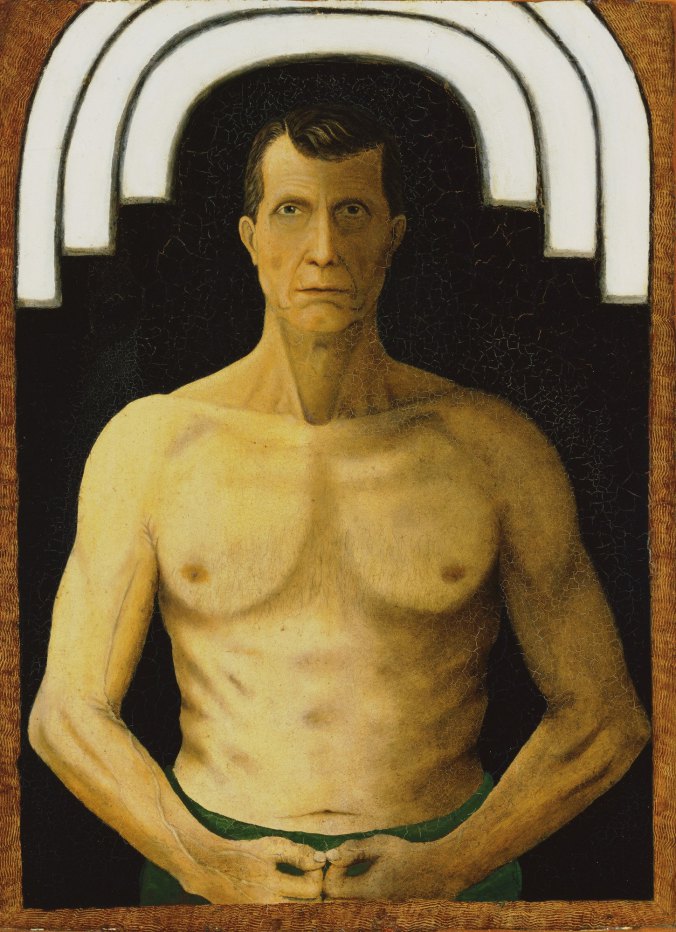

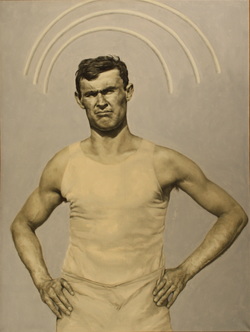

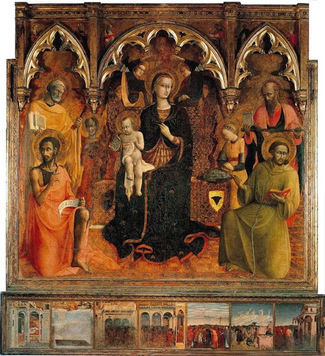

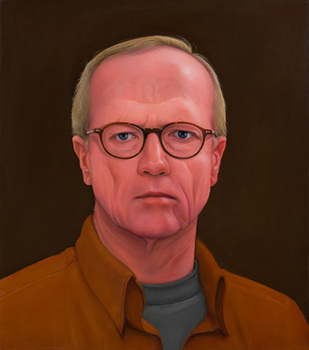

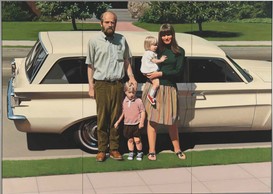

Robert Bechtle, "'61 Pontiac"

Robert Bechtle, "'61 Pontiac" Titles should act as descriptions to aid in the identification of individual works: the exasperating "untitled", of course, should be avoided at all costs. Perfect titles include "Ocean Park #24", "Woman II", and "'61 Pontiac".

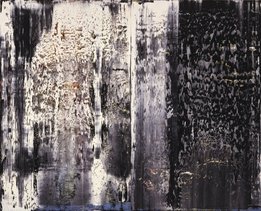

Titles can be be evocative as long as the feeling/sensation is the same as the image and is not meant as an augmentation: see Richter's "January".

Titles can be be evocative as long as the feeling/sensation is the same as the image and is not meant as an augmentation: see Richter's "January".

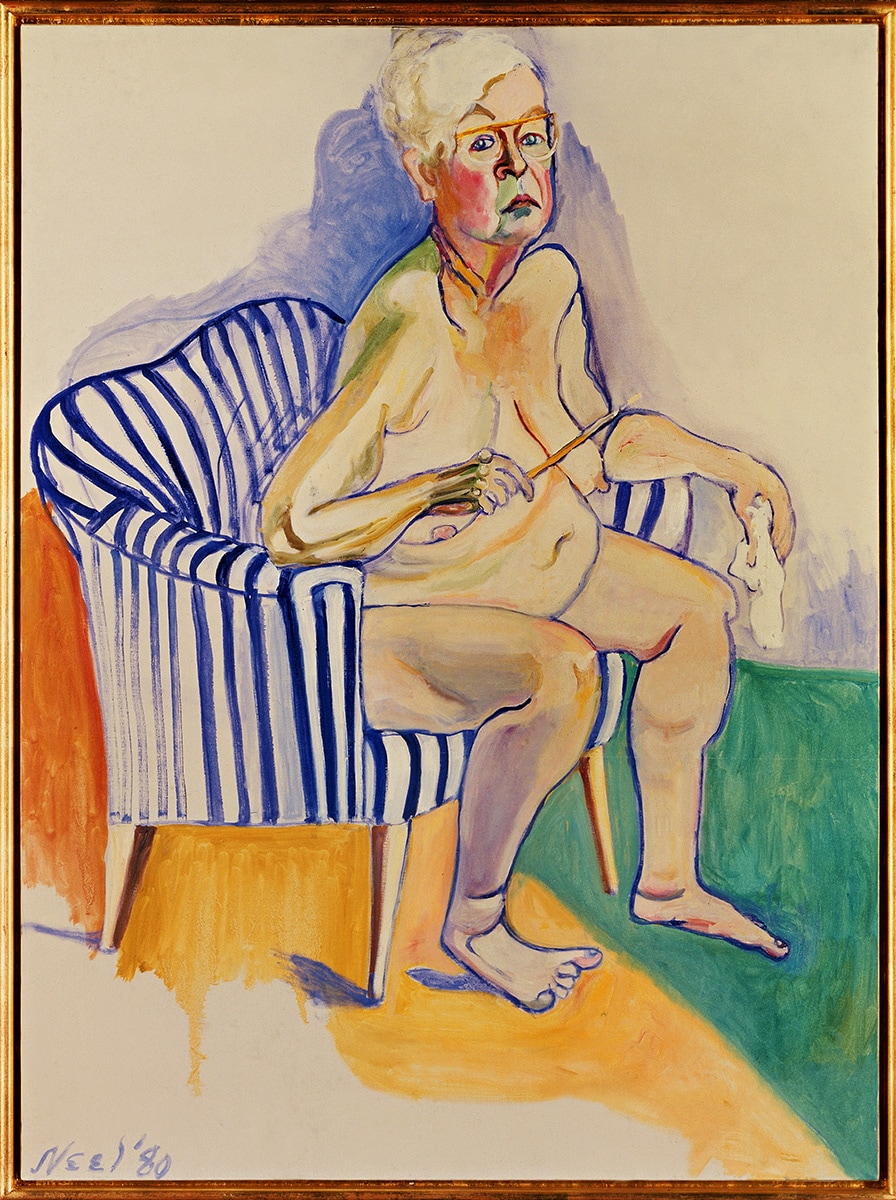

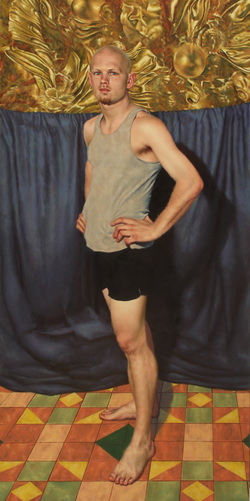

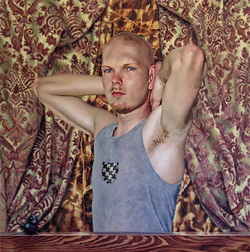

Gerhard Richter, "January"

Gerhard Richter, "January" Like "January", I think "Scrub on a Hill" is both descriptive and evocative. "Scrub" is such a great word! In horticultural terms, it describes untended and unwanted growth, the detritus of man's interaction with the natural landscape.

That is very close to the underlying investigation (content) of all my landscape drawings and paintings.

Descriptive indeed!

That is very close to the underlying investigation (content) of all my landscape drawings and paintings.

Descriptive indeed!