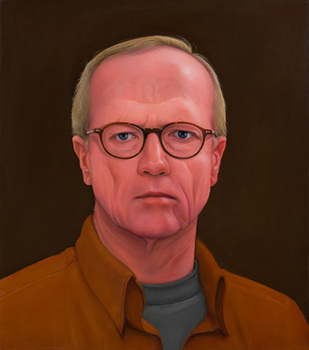

William Beckman, "S.P.,Brown on Brown", 2013

William Beckman, "S.P.,Brown on Brown", 2013 Last spring, I saw the self-titled William Beckman exhibition at the Forum Gallery in New York. I have seen very few Beckman's in person and it was a thrill to study the approximately 20 paintings and drawings up close and in the privacy of the beautiful Forum Gallery. Represented in the show were his three primary subjects: clinical and direct bust portraits of himself and loved ones, female nudes in the artist's personal space, and healthy northern midwest farm-scapes.

In over 30 years of working with the same subjects and themes, Beckman's oeuvre has changed little and a lot. He is still a formidable and demanding investigator of his subjects, exposing as much definition of their reality as possible. And while he is still an exacting draughtsman, he is less intent on depicting every facial pore and thread-count fabric as he is in mining the reality of the subject's presence. His work is, dare say, more abstract; he is more interested in the essence of the subject than the appearance, so we come to understand the subject by experiencing the solid plastic qualities of the head, for instance, or by the depth of the siena in the shirt.

As with most mature artists, Beckman's work continues to evolve towards his aesthetic critical mass: the least amount of form required to express his unique content. Besides unnecessary detail, for example, his portraits are now almost totally void of environment - his subjects don't need context to exist, so he eliminates it. Some people miss the technical bravura of the detail, but it would be dishonest of him to retain something that didn't support his content just to demonstrate an exceptional skill.

In over 30 years of working with the same subjects and themes, Beckman's oeuvre has changed little and a lot. He is still a formidable and demanding investigator of his subjects, exposing as much definition of their reality as possible. And while he is still an exacting draughtsman, he is less intent on depicting every facial pore and thread-count fabric as he is in mining the reality of the subject's presence. His work is, dare say, more abstract; he is more interested in the essence of the subject than the appearance, so we come to understand the subject by experiencing the solid plastic qualities of the head, for instance, or by the depth of the siena in the shirt.

As with most mature artists, Beckman's work continues to evolve towards his aesthetic critical mass: the least amount of form required to express his unique content. Besides unnecessary detail, for example, his portraits are now almost totally void of environment - his subjects don't need context to exist, so he eliminates it. Some people miss the technical bravura of the detail, but it would be dishonest of him to retain something that didn't support his content just to demonstrate an exceptional skill.

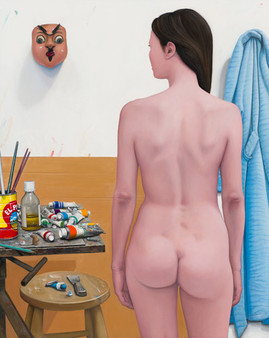

William Beckman, "S.L. #1 (El Pico)", 2011

William Beckman, "S.L. #1 (El Pico)", 2011 New to Beckman's oeuvre are the still life paintings of his palette environs. I'm not usually a fan of the artist's working environment as subject matter because it becomes too easily a metaphor for creativity. But here Beckman uses it as an investigation of the tactile. The subject transcends the appearance of paint tubes into the physicality of pigment and their constraints (tubes). We are less aware of the subject as tools of the painting trade and more concerned with them as unusual physical entities. Of special note (and, I'm sure, his aspiration) is that his coffee cans demand as much presence and gravitas as Jasper Johns'.

William Beckman, "Studio Five", 2010-12

William Beckman, "Studio Five", 2010-12 Not necessarily new, but certainly evident in his new work, are homages to his friend, Gregory Gillespie. Beckman and Gillespie were good friends for many years: they painted each other's portraits and shared an intense interest in visual reality despite approaching it from very different directions. While Beckman's, as we said, is very clinical and detached, Gillespie's work was intensely psychological and surrealistic. While Beckman hides the struggle in his work, Gillespie exposed it. Gillespie committed suicide in 2000.

It's interesting to see how artists are influenced by each other when we compare the works of two good friends. Direct visual references to Gillespie in Beckman's latest work include the use of masks, dimension coming off the canvas in the form of paint ooze and surface irregularities like wall punctures and screws, and heavy outlines in the still lifes. Gillespie used the latter two regularly (along with other devices) to upend the expectations of the illusionistic picture plane and question our conventions of reality.

It's interesting to see how artists are influenced by each other when we compare the works of two good friends. Direct visual references to Gillespie in Beckman's latest work include the use of masks, dimension coming off the canvas in the form of paint ooze and surface irregularities like wall punctures and screws, and heavy outlines in the still lifes. Gillespie used the latter two regularly (along with other devices) to upend the expectations of the illusionistic picture plane and question our conventions of reality.