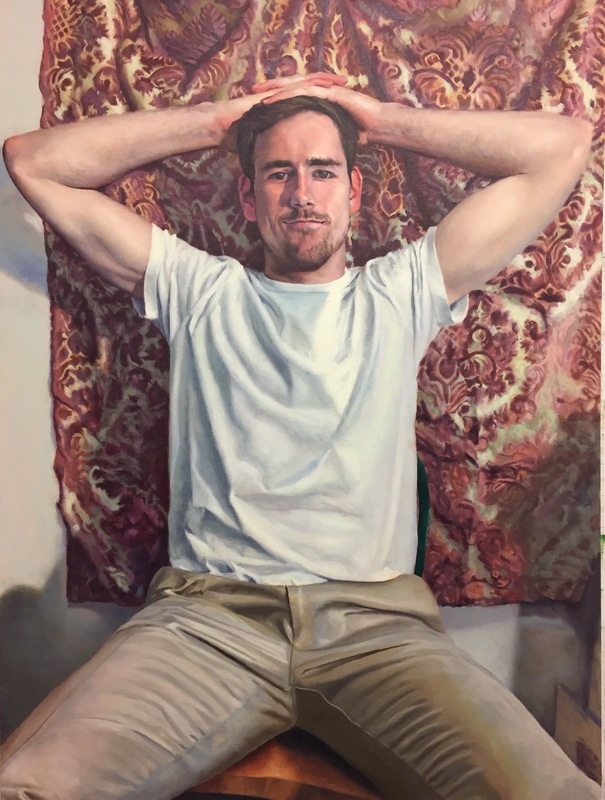

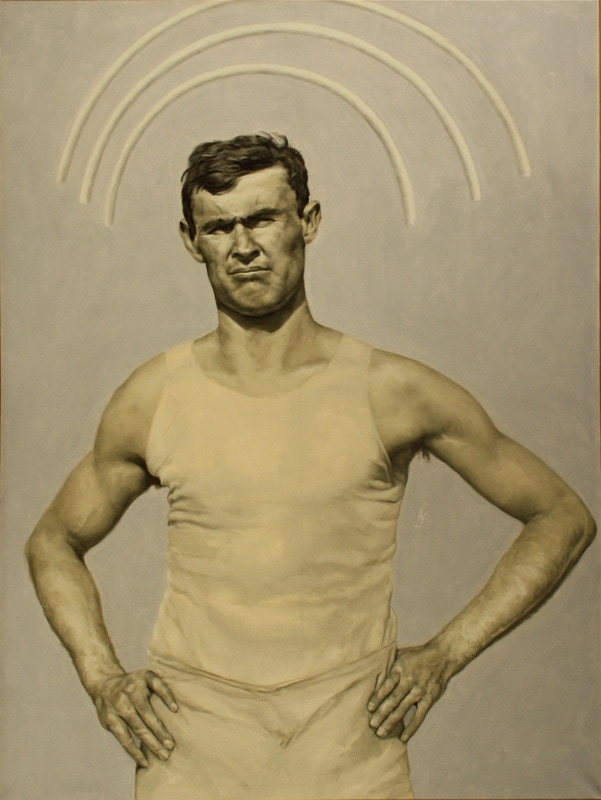

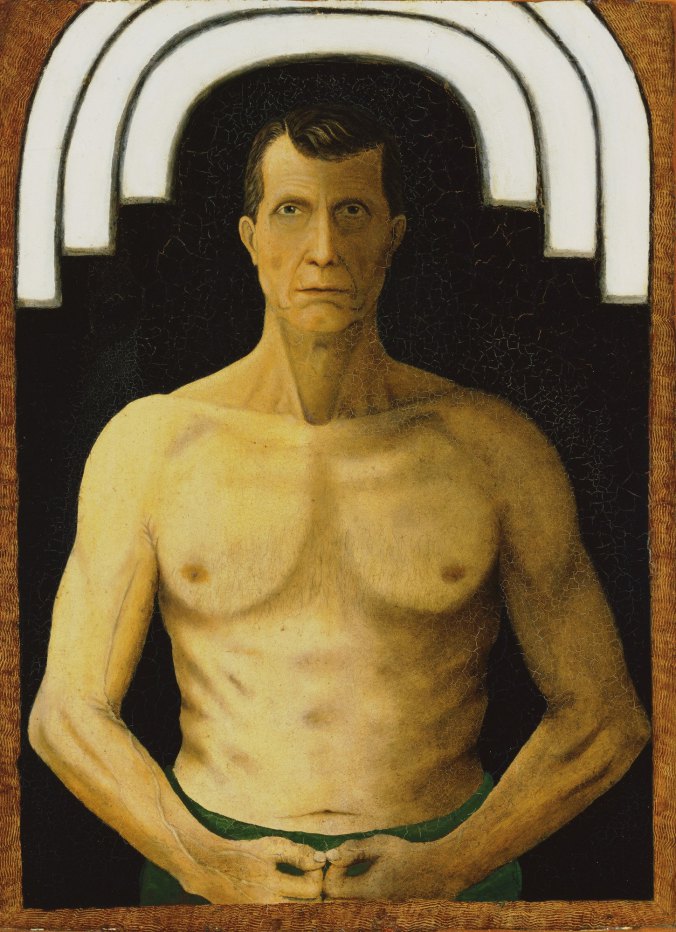

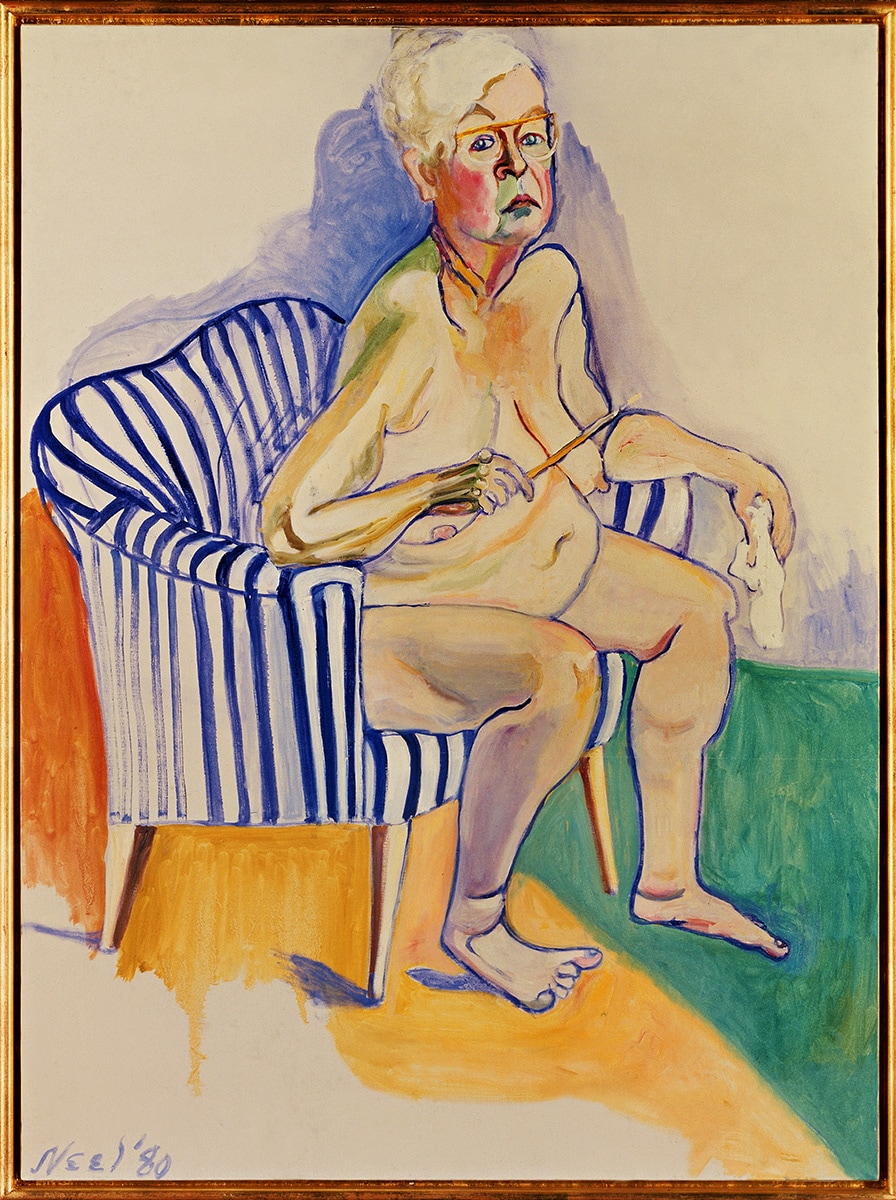

| "Hartley" represents the latest in my "homage" series of paintings. It is a direct reference to Alice Neel's 1964 painting of her younger son, Hartley. Mine is an oil on canvas, 40"x30",with my son, Murphy, in the title role. Most recently, I paid direct homage to Hans Holbein in "The Dead Christ". Previously, my figure studies have directly referenced Gregory Gillespie, Thomas Eakins, John Kane, and Walt Kuhn. "Direct reference" is not a euphemism for stealing: homage is not a passive and parasitic activity. It is founded on a deep and immediate connection on the basis of form, content, and inspiration. The first time I saw Walt Kuhn's "Roberto", I knew that he understood me: he wears my shoes when he paints. Kuhn's ideas are worth revisiting through my eyes because our views of the world are so similar. For me, homage is not about style because neither is inspiration. My major influences run the gamut of aesthetic approaches, including Surrealists (Gillespie), Realists (Eakins), Naivists (Kane), and Abstractionists (Kuhn). Neel has always been a favorite painter of mine and an inspiration, partly because I see her as the patron saint of Late Bloomers: she did not achieve broad success and recognition until well into her 50's. There might still be hope for me. I met Neel in the mid-70's when she visited the Painting program at Washington U, acclaimed then as a national treasure and looking every bit like the sweet old Granny of her infamous self-portrait; only clothed. The sweet old Granny regaled us all afternoon with stories of her bohemian lifestyle in mid-century New York including, multiple affairs, scandals,and even brushes with the law. Neel's life was trying at best and I don't equate my life experiences with her's. What I admire and respect is her determination and commitment to her painting ideals in spite of life's adversities: her tumultuous love-lives, getting caught up in the Red-Bait scare of McCarthyism, being a welfare mother raising two sons, and the emotional costs of losing two daughters; one to an early death and one to parental kid-napping. I also admire Neel's ability to instill in her subjects an animated humanity; a gestural physicality demanding our responce. As in all of her portraits, Neel's "Hartley" transcends the character of the individual to address the subject in universals. Some people refer to any image of a figure as a portrait. That, of course, is incorrect. A portrait attempts to express uniqueness of the individual; to say something about the character of the person through examination of carriage and appearance. Most figurative work, on the other hand, is about universals: the image of the figure representing an aspect of the human condition - a mirror to our collective soul. As a figure painter and a portraitist, I normally do one or the other; the universal or the individual. Neel almost always manages to do both. Eakins often accomplished both, as did Holbein: Sargent never did (he perfectly captured the individual without empathy). |

Just as Neel's "Hartley" has always been read as the artist's son representing the universal "young man", so Murphy as my "Hartley" is more of a concept than a person. There is a little personal Murphy there, but not much: he is meant to portray a type, a state of being. It is my attempt at the individual/universal.

There are a number of conscious references in my homage to Neel's "Hartley. Both Hartleys are the artist's younger son. They are in the same pose. They are attired in white T's and khakis which are both timeless and time-referenced. There's a suggestion of Brancusi's Male Torso. It is an obvious studio environment with studio chair, fabric, and homosote. It is the occasion of a child visiting the studio of a parent.

There are a number of conscious references in my homage to Neel's "Hartley. Both Hartleys are the artist's younger son. They are in the same pose. They are attired in white T's and khakis which are both timeless and time-referenced. There's a suggestion of Brancusi's Male Torso. It is an obvious studio environment with studio chair, fabric, and homosote. It is the occasion of a child visiting the studio of a parent.

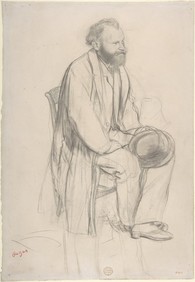

Edgar Degas, "Manet in the Studio"

Edgar Degas, "Manet in the Studio" Not to make too much of it, but the painting tradition of a visit to an artist's studio is a reference to intimacy. Whomever is visiting the studio is entering the artist's private domain and assuming some responsibility for the artistic output. Think Degas' drawing of Manet, Madame Cezanne, and most of William Merritt Chase's oeuvre.

In this case, the parent/child relationship is reversed as Hartley is visiting the parent's studio in direct support of her/his professional objectives, a job usually undertaken by the parent. But is a child's visit to the studio, even an adult child, ever really voluntary? As in all parent/child intimacy, there is a subtext of obligation in Hartley's visit.

In this case, the parent/child relationship is reversed as Hartley is visiting the parent's studio in direct support of her/his professional objectives, a job usually undertaken by the parent. But is a child's visit to the studio, even an adult child, ever really voluntary? As in all parent/child intimacy, there is a subtext of obligation in Hartley's visit.