Bartolemmeo Bulgarini, "the Assumption of the Virgin with St. Thomas Receiving the Girdle" 1360's

Bartolemmeo Bulgarini, "the Assumption of the Virgin with St. Thomas Receiving the Girdle" 1360's When my wife and I first travelled to Italy in the early 1980's, many people told me that we had to go to Siena: it was an aesthetic experience unlike any other. We were primarily committed to Rome because of my work with Tyler School of Art but we arranged a long weekend outside of Rome and chose Florence over Siena, because of Florence's obvious influence on Renaissance art and philosophy. I've never regretted that decision and Florence is, of course, not to be missed.

But almost 30 years later, I had the opportunity to spend 24 hours in Siena and I was totally smitten. As soon as I entered the first of the major civic museums, Palazzo Pubblico, I knew I was home. The connection to my personal aesthetic and the works of the Sienese masters was immediate, overwhelming and only strengthened as I subsequently visited the Cathedral and Baptistry, the Pinacoteca Nazionale, and the Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala. It didn't take long to realize that I am Sienese! It was a feeling akin to those who discover in adulthood that they're the victim of a maternity ward baby-swap! How had I never known? Would I have had the same epiphany had I visited 30 years earlier? Would my years of artistic searching been eased?

But almost 30 years later, I had the opportunity to spend 24 hours in Siena and I was totally smitten. As soon as I entered the first of the major civic museums, Palazzo Pubblico, I knew I was home. The connection to my personal aesthetic and the works of the Sienese masters was immediate, overwhelming and only strengthened as I subsequently visited the Cathedral and Baptistry, the Pinacoteca Nazionale, and the Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala. It didn't take long to realize that I am Sienese! It was a feeling akin to those who discover in adulthood that they're the victim of a maternity ward baby-swap! How had I never known? Would I have had the same epiphany had I visited 30 years earlier? Would my years of artistic searching been eased?

Simone Martini, "The Annunciation" 1333

Simone Martini, "The Annunciation" 1333 Not fully aware that they were Sienese, I have always been influenced by the works of Simone Martini and Sassetta (it turns out a lot of what was attributed to Sassetta is now determined to be by another Sienese artist called The Master of the Osservanza). But in Siena, my aesthetics were being confirmed everywhere I looked: I discovered or rediscovered Bulgarini, Lorenzetti, Vecchietta, Matteo di Giovanni, Giovanni di Paolo, and many more.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, "The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple", 1342

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, "The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple", 1342 So what is distinct about Sienese art? Artists like Duccio, Lorrenzetti and Martini were at the forefront of the Renaissance revolution but veered from the path of full humanist discourse, the route of their rivals the Florentines. What remained for generations of Sienese artists is a fascinating combination of Gothic spirituality and Renaissance earthly specificity.

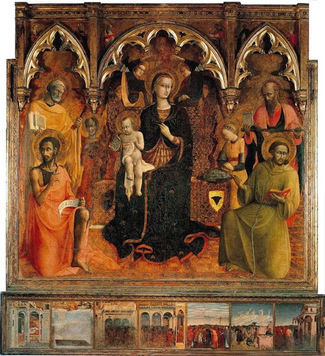

Sassetta, "The Virgin and Christ Child with Saints", 1430-32

Sassetta, "The Virgin and Christ Child with Saints", 1430-32 The Sienese retained the insistence on the earthly materiality of the figure (subject) while continuing the Gothic idea of divine space for the ideal. From Lorenzetti and Martini on, the Sienese subjects became more and more grounded in earthly reality while the environs remained other-worldly.

While the Florentines strived to integrate their subject (man) to a recognizable worldly environment, the Sienese intentionally separated them. The Florentines, like the prevailing Renaissance philosophy, wanted man to be fully involved in and master of his earthly home. The Sienese, I think, recognized man's baseness and purposefully chose a context for man's higher achievements that was not familiar. This is what I connect with.

My work has always been about presenting the trials of the everyman but elevating those challenges from the individual to the ideal: we are defined by the material reality of our physical existence, the corporeal, but mere presence is not sufficient justification for existence.

While the Florentines strived to integrate their subject (man) to a recognizable worldly environment, the Sienese intentionally separated them. The Florentines, like the prevailing Renaissance philosophy, wanted man to be fully involved in and master of his earthly home. The Sienese, I think, recognized man's baseness and purposefully chose a context for man's higher achievements that was not familiar. This is what I connect with.

My work has always been about presenting the trials of the everyman but elevating those challenges from the individual to the ideal: we are defined by the material reality of our physical existence, the corporeal, but mere presence is not sufficient justification for existence.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, "The Annunciation" 1344

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, "The Annunciation" 1344 The Sienese relegated their concern for the material to their figures who were as much of this world and governed by the laws of physics as Piero della Francesca's (who was greatly influenced by Sienese painting). Emphasizing the mystical or decorative in the environs, however, the Sienese invented figures connected to this world but not of it. These other-worldly environs are achieved with the use of ethereal gold leaf, decorative patterning, or stylized architecture and landscape. This juxtaposition of the emphatic corporeal presence of human figures in a referential but unrealized space is specifically Sienese.

What this conveys in the Sienese paintings and, I hope, in mine is that the realism in the figures is separate from the realism of experience: we are defined by our materiality but also by our aspirations.

What this conveys in the Sienese paintings and, I hope, in mine is that the realism in the figures is separate from the realism of experience: we are defined by our materiality but also by our aspirations.

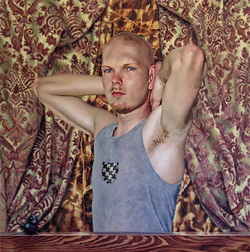

John Troy, "St. Anthony", 48" X 48"

John Troy, "St. Anthony", 48" X 48" Another less-weighty but no-less exciting connection to my Sienese fraternity is our shared reliance on the red/green scale for flesh: it was exhilarating to see so much green flesh in one town!

My most conscious Sienese painting since the epiphany is "St. Anthony"; not a dramatic change in my oeuvre but probably a little too referential.

My most conscious Sienese painting since the epiphany is "St. Anthony"; not a dramatic change in my oeuvre but probably a little too referential.